Interview with Marta Bellingreri from Alarm Phone: six years on the side of humanity

“The first phone call I received came while I was living in Jordan. Fortunately it was not a dramatic case, but I will always remember it. Because until Alarm Phone was born I was suffering; being always around for my work I couldn’t be part of a collective in a stable way, I couldn’t feel part of something, I was missing a piece of my story. At that moment I felt part of a big Euro-Mediterranean family, with activists from Tunisia to Berlin, from Morocco to Manchester. No matter where I was, I could help. The hardest phone call, however, I still remember: January 2016. Unfortunately they were not saved. And it is dramatic to hear people on the phone asking for help, then lose contact, knowing what is going to happen or has already happened. I stayed 24 hours in total blackout”.

The speaker is Marta Bellingreri, journalist and researcher. Since the beginning she has been part of the Alarm Phone project, the number +334 86 51 71 61 that boats in distress or migrants on land borders in difficulty call for help.

“The project was born between 2013 and 2014, following the two tragic events of October 2013: the terrible shipwrecks of the 3rd and 11th of that year. In particular for the one on 11 October, when for six consecutive hours people on board a boat in difficulty called the Italian and Maltese authorities who did not answer: 250 people drowned, of Syrian nationality. After that tragedy the question arose: what could change? How many lives could have been saved if there had been someone who could have been warned from on board during those six hours to put pressure on the authorities? For a year there were a series of meetings of activists – who knew each other and had crossed paths in other thematic networks on freedom of movement, border militarisation and anti-racism – between Germany, Tunisia and France. On 11 October 2014, exactly one year after the tragedy, the number became active and never went out again”.

A line active 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, with people alternating in 8-hour shifts. People can change shifts, but the number never stops. And since then the project has grown a lot.

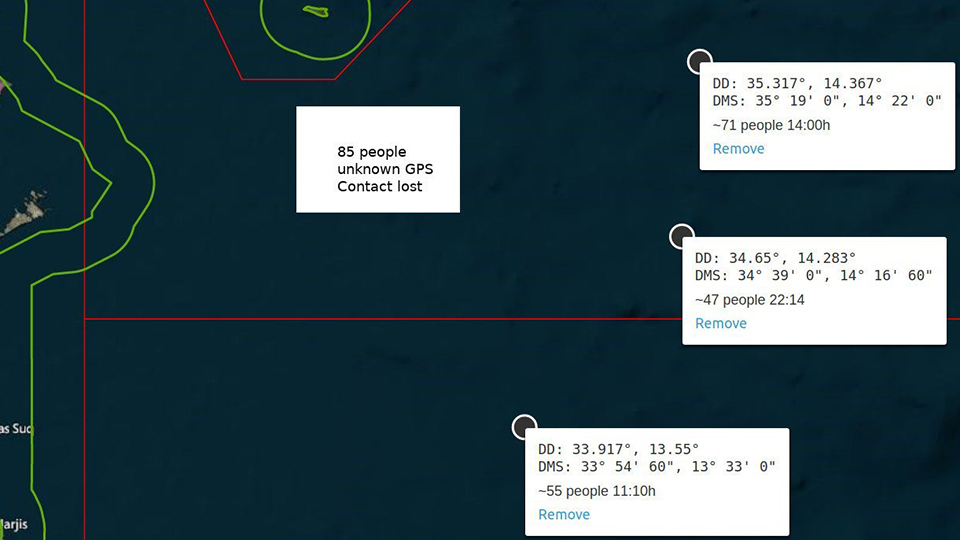

“In the first months there were not many calls – says Marta – then word of mouth started, especially among migrant communities. Now we are structured in three monitoring zones: Western Med, which covers the area between Morocco and Spain and, in particular in the last months, the route between Senegal and the Canaries, Central Med, which covers the routes from Libya and Tunisia to Italy and also Algeria – Sardinia, and finally Aegean Sea, for the route Turkey – Greece, but sometimes also Lebanon – Cyprus. In total there are at least 80 people taking turns, but there are also 120, with the new ones receiving training, technical and action training. When we receive the call, we notify the competent Coast Guard, whether Maltese, Italian, Greek or Spanish, depending on the SAR areas concerned. With the Libyan Coast Guard it is different: we tend not to call them, as we have a clear position against the fact that migrants are then brought back to Libyan centres, except for special situations, with all the difficulties of the case, even if they do not speak English and do not answer”.

Alarm Phone has kept a memory and track of its work over the years. On their website (click here[link: https://alarmphone.org/it/) there are data, reports, testimonies and stories collected in these years by the groups that are currently active in Morocco, Tunisia, Italy, France, Germany, Spain, Turkey. In addition to the teams, there are contact persons in Libya, Greece and Algeria.

Since the beginning, however, year after year Alarm Phone‘s actions have evolved and others have changed.

“Calls change, for example in 2019 the majority came from Spain and Morocco, in 2020 from Libya. They are all different calls: at the Greek-Turkish border they have whatsup, they can send voice messages and coordinates, and there is very strong contact. From Libya, on the other hand, they use thuraya, in the middle of the sea, you can’t hear anything. And finally from Senegal and Morocco they have old phones, it is very difficult to find the location, in fact we launched some time ago a campaign to collect used smartphones. And things in general have changed a lot in the last two years with the increasing criminalisation of solidarity. I myself have had a lower profile, dealing less with phone calls and more with reports and translations. And we have changed our communication: before we didn’t mention our operations, now we do. A media team is working on this, while a legal team is working on collecting complaints of failure to respond to the European Court of Human Rights, because we have to react to this climate.”

An experience, intense and deep. Sometimes very hard. “Every year we manage to find ourselves twice, around, this year – because of Covid – only once, in September, in Berlin. And it’s the first time I haven’t felt the need for psychological support, because it’s hard, the risk is to feel guilty, to wonder if you were wrong, or you could have done more,” says Marta.

That together with everyone at Alarm Phone reacts by continuing to make itself useful, also increasing the impact. “The From the Sea to the City project was born, with the desire to create a network of welcoming cities, to think beyond the moment of emergency, which was already there in Germany and started in Italy, with Palermo and Naples. And we are also part of what we call the ‘civilian fleet’, in coordination with the NGOs working at sea where there are no institutional means of rescue, or where they are not moving”.

by Christian Elia