The border as destiny

There are monuments that celebrate the past, others that were created so that the past does not have to repeat itself. Similarly, without being the work of artists or governments, there are symbolic places that end up carrying a message with their very history.

This is the case of the town of Brennero, an eternal place of borders, of passage, of meeting and sometimes of clash.

The town of Brennero, a diffuse municipality of 2,000 inhabitants, is a border of great symbolic significance for the Tyroleans, because the Brennero border has divided North and South Tyrol for a hundred years.

Caravans and emperors, dictators and traders have passed through the pass, which has always been the border.

It is symbolic for the South Tyrolean emigrants who were forced to leave their homeland during Nazi-Fascism, then for the post-war emigrants who emigrated to Germany because of poverty and unemployment, and then from 1990 onwards for the new immigration.

The province of Bolzano has welcomed around 50,000 migrants in 30 years, but many thousands of refugees and migrants have crossed the province to reach a northern European country. They have crossed the Brenner Pass for this purpose, but since 2015 it has become increasingly difficult. The Brenner Pass has become an almost insurmountable wall for them, and hundreds are sent back every year.

Because there are places that seem to have the border as a destiny, but it is always human beings who put barriers where there have always been passages. The Brenner Pass is the lowest pass to cross the barrier of the Alps, between those black rocks that have passed the Roman legions of Drusus and Tiberius and about sixty German emperors on their way to Rome to be crowned by the pope.

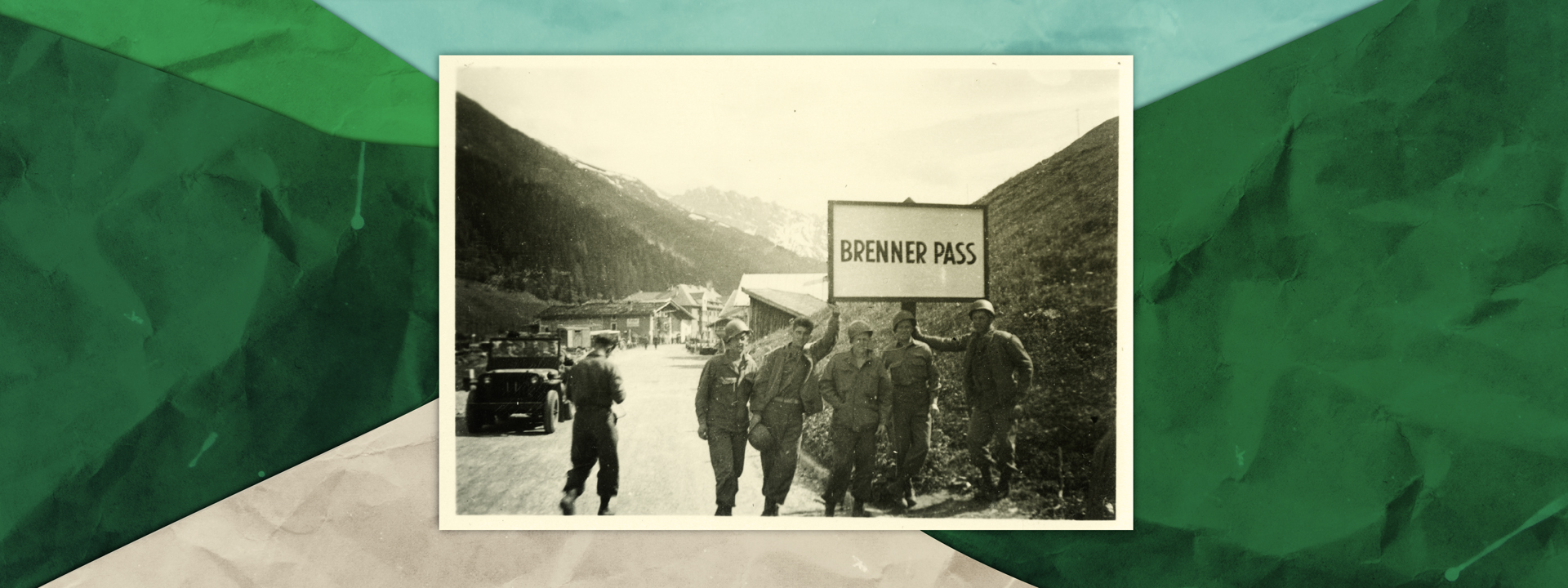

It was a tiring and treacherous journey through the narrow gorges of the Eisack, populated by brigands. Goethe arrived there on 10 September 1786, and the railway arrived on his journey to Italy in 1867. In 1919, the traumatic division of Tyrol brought the border line to where it had never been before: the Brenner became the border between Austria and Italy. South Tyrol was annexed and a few years later the forced Italianisation of the region by Fascism began.

In 1940, Hitler and Mussolini met at the Brenner Pass. Like all borders, the pass was a smugglers’ area, and smugglers moved nimbly along the mountain paths around the pass. To take undocumented people from one country to another, separate fees were paid for adults and children.

In 1995, the governments of Italy and Austria put an end to that border between their states, in a spirit that anticipated a united Europe and those agreements that today – for European citizens under 30 – are taken for granted, such as the free movement of people and goods.

Once it was only the dream of a few brave people, who remembered conflicts and divisions, or dictators’ agreements. Today it is a reality for millions of people, but it remains a border for many people who, today as then, cross borders in search of a better life.

by Christian Elia