Between yesterday’s and today’s divisions

Every year, all over Europe, 8 November is a date to celebrate. The fall of the Berlin Wall, which separated cities, families and worldviews for decades, collapsed under the pressure of history in 1989.

Much time has passed since then, many things have changed, some things have become much worse.

One of them is the very idea of that wall. At the time, all those who hoped that the wall would fall were given a fundamental right: the right to freedom.

Today, many years later, many new barriers have sprung up between the borders of Eastern Europe, which in 1989 became a common political, social, cultural and economic area.

Hungary’s border fence was among the first to rise, in 2015, when the wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan had led to the highest number of asylum applications received in relation to the population: 1770 applications per 100,000 inhabitants. Hungary began the fencing of its borders with Serbia and Croatia: 289 kilometres of iron and barbed wire.

What would yesterday’s wall and today’s wall say to each other if they could talk? Before the Berlin Wall, already after the Second World War, the Iron Curtain was born, which for millions of people meant a scar in the heart of a Europe that – even in the bloodiest wars – had never known barriers to movement.

Every year, all over Europe, 8 November is a date to celebrate. The Europe of the 1930s was a network of relationships, travel, encounters, but after 1945 a physical and ideological rift was created, dividing what had always been crossed by roads.

Today, as then, it would be interesting to see what the old and new barriers would tell each other.

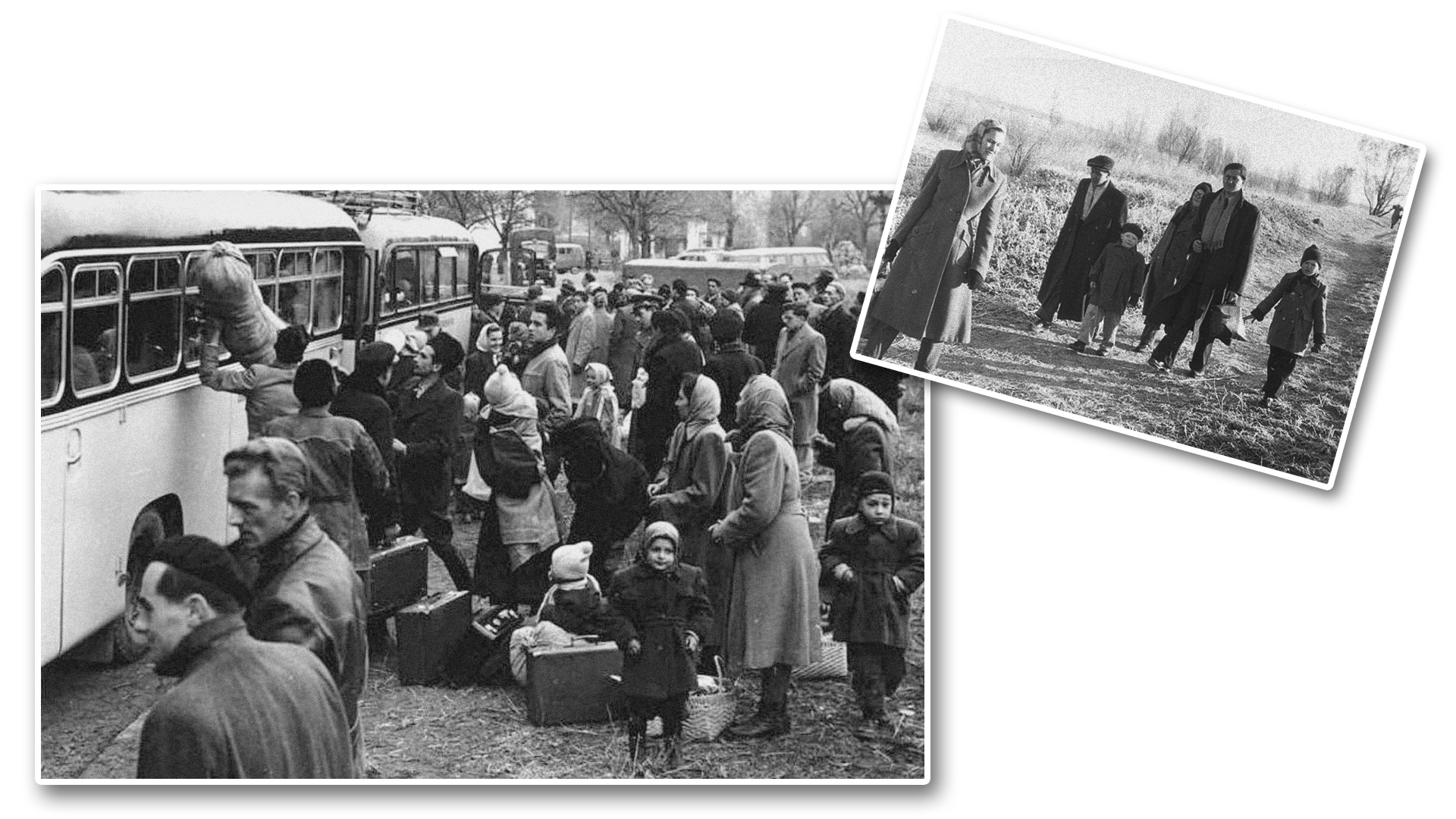

They would talk about 1956, when more than 250,000 people fled Hungary to countries that welcomed them, respecting their desire for a different life. That curtain was an obstacle, which for those people was an obstacle.

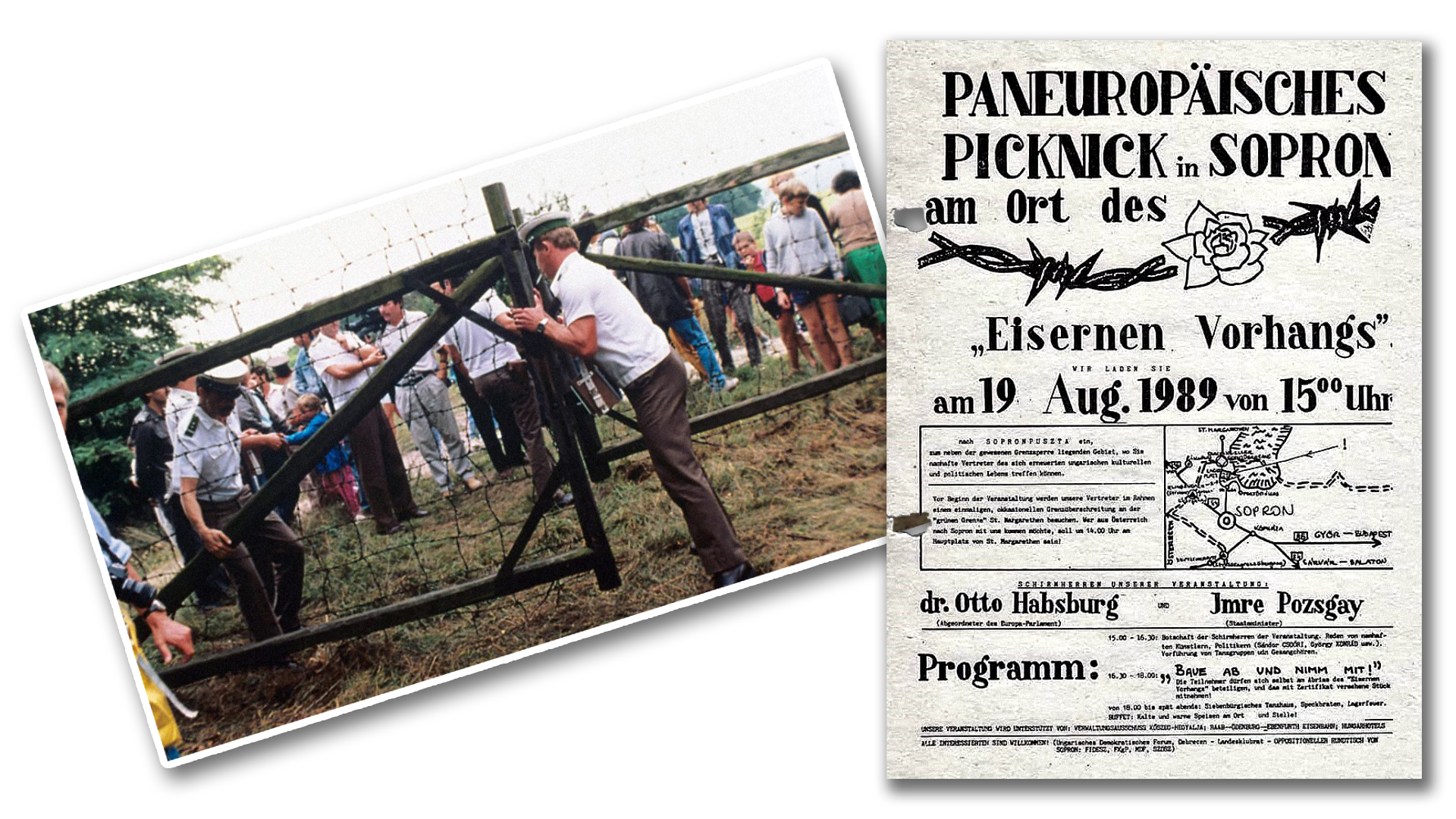

Or they would tell each other about that picnic that suddenly helped to accelerate a historical process. On 19 August 1989, a large number of people met at the Hungarian-Austrian border, in a border clearing next to the road from Sankt Margarethen im Burgenland to Sopronkohida, a small village on the other side of the border, a few kilometres from the town of Sopron.

Thousands of people poured in from both sides of that border, until all that was left was to open it. Today that area is a destination for tourists and travellers, today there are companies with employees from both countries.

Maybe today’s barrier would ask a lot of questions of those of yesterday, but the answer would probably always be the same: sooner or later barriers fall, because people – for the most diverse reasons – have always moved and will continue to do so, in search of a better life.

by Christian Elia