Getting lost in the streets of Rhodes is like taking a trip with a time machine. For a long time now, even though the global pandemic has changed the priorities of the international media, the Greek islands have been mentioned only when reporting on today’s migrants, refugees fleeing wars, hunger and poverty.

While the whole world was worried about what was happening in Afghanistan this summer, many people who had fled from that war were waiting to know their fate in the collection centers, and many of them had come from Afghanistan.

One of the problems of our way of narrating is that of always putting the facts in the present tense, as if the phenomena had never existed before.

The streets of Rhodes, the hospitality of its people, its history tell us how the position of this beautiful Greek island has always made it a land of passage, of encounters and clashes.

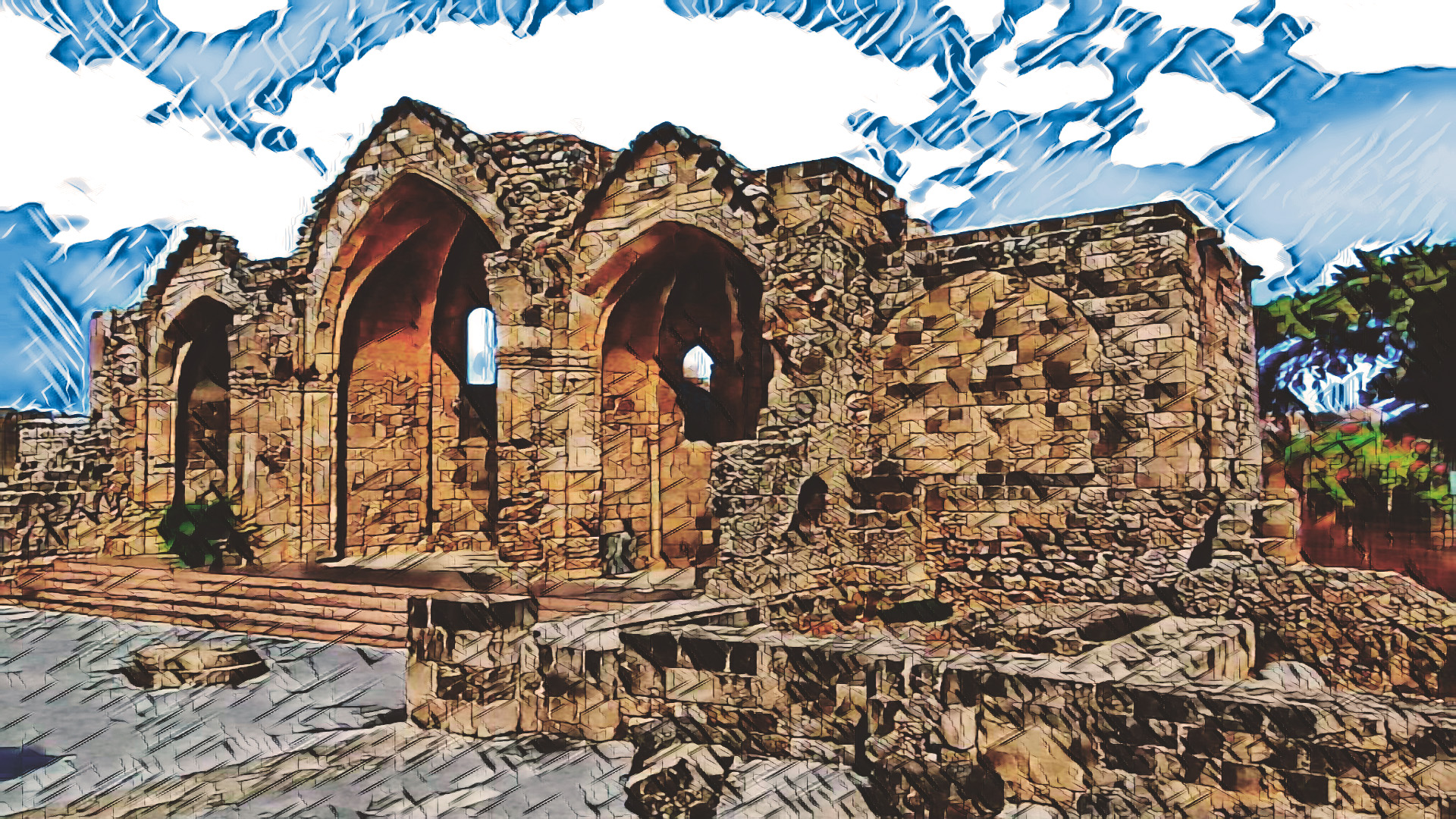

The old city, which Unesco protects as a world heritage site, is proudly enclosed within mighty walls, and inside contains an extraordinary fusion of different architectural styles: classical, medieval, Ottoman and Italian. Each style is a reminder, a tale, of previous passages on the island.

The Knights’ Quarter, an area of the old city used as the headquarters of the Knights of St. John, who ruled Rhodes between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, or the Palace of the Grand Master, a magnificent palace built in the fourteenth century on a former Byzantine fortress as the seat of the highest authority of the Order of the Knights of St. John. The interior, damaged by an explosion in the nineteenth century, was rebuilt in the fascist era during the Italian occupation of the island.

And then the Mosque of Suleiman the Magnificent, with its characteristic pink walls, was built in the 16th century to commemorate the victory of the Ottomans over the Knights. Acropolis of Rhodes, the site of the ancient Hellenic city, two kilometers from the old city, which preserves the remains of a stadium of the second century AD and a theater that was used for the lessons of the school of rhetoric. Up to the lighthouse of Agios Nikolas, built by the French, which is located at the entrance of the marina of Mandraki, and the Kalithea baths, designed by the Italian architect Pietro Lombardi and inaugurated in 1929, a sumptuous spa complex in art deco style with an impressive patio and an abundance of pavilions, halls, corridors, colonnades, staircases and mosaics, all immersed in a natural setting of extraordinary beauty.

These wonders, which the whole world admires and visits every year, are memories of real invasions, which weapons in hand marked the history of the island, but also left an extraordinary heritage today.

And instead we end up calling invasions the journeys of desperation of thousands of people fleeing, who do not arrive armed, on the contrary, but with the few things they managed to take from their homes before fleeing.

They too would have something to give in the form of culture, exchange, intellectual wealth. They too should be given the opportunity to learn and teach, as has always been the case in Rhodes’ history.